The

Watt family had moved into No. 5 Fennsbank Avenue, Burnside on Glasgow’s south

side on the 13th of July 1956, and had looked forward to moving to

an area which they considered a step up the social ladder. A mere two months

later, on the 17th of September 1956, 3 members of the Watt family

would be murdered in their beds as they slept, in a horrific and apparently

motiveless crime. In the house that night was Marion Watts (45), her daughter

Vivienne (17), her sister Margaret (41) and Vivienne’s friend Deanna Valente

(19). Deanna had spent the evening with Vivienne listening to the ‘Hit Parade’

on Radio Luxembourg, but left the house at about 11.40pm. Luckily or unluckily,

Marion’s husband William Watts, the owner of Denholm Bakeries in London Road

Glasgow, was absent on the night of the murders as he was enjoying a fishing

holiday at the Cairnbaan Hotel, near Lochgilphead.

Two

days before the murder of the Watt family, Peter Manuel had broken into a

neighbouring house, No.18 Fennsbank Avenue, owned by retired sisters Margaret

and Mary Martin. While stealing very little, he enjoyed turning the house

upside down, dirtying their beds with his boots, burning the carpets with a

cigarette and poured a can of soup over the floor, before stealing a pair of

nylon stockings which he would later use to cover his hands in his next endeavour.

|

| Marion Watts and her daughter Vivienne standing by William Watts maroon Vauxhall with labrador Queenie |

|

| Margaret Brown |

Using

the Martins house as a base, Manuel crept over to the Watts home in the early

hours of the 17th of September. After smashing the front door glass

panel he proceeded to Marion Watt’s bedroom and shot her in the head with a .38

revolver. He then fired two shots into the body and head of her sister Margaret

Brown who was sleeping next to her, the second shot suggesting that she had

stirred after she heard the gunshot that killed her sister. Mrs Watt’s

nightdress had been pulled up and her sister’s pyjamas trousers had been torn.

Manuel then moved on to Vivienne’s room, where there were signs of a struggle,

it is probable that she had awoken at the gunshots the killed her mother and

aunt. Vivienne had been battered around the head before being shot, her hands

had been tied behind her back and her pyjamas bottoms had been ripped. Before

leaving the home Manuel covered each of the bodies with bed sheets and calmly

smoked a cigarette before trampling it into the carpet.

|

| Police guard the Watt house |

The

bodies lay undiscovered until Mrs Helen Collison, 47, the Watt’s domestic help

arrived at 8.45am and could not get in – she told the press: “I usually just

walked in because he door was not kept locked. But to-day the back door would

not open. I went to Vivian’s window and knocked on it. There was no answer.’ It

was then that Mrs Collison discovered that the glass of the front door was

broken, she then alerted the next door neighbour, Mrs Valente, Deanna’s mother.

The two women ran back to the Watts house where they encountered the postman,

who put his arm through the broken panel and unlocked the door from the inside.

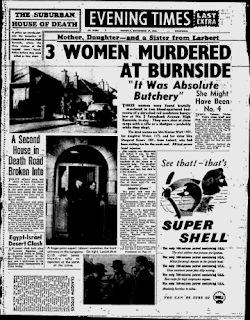

It was then that the terrible crime was discovered, one officer described the

scene as ‘absolute butchery.’

After

the police were called, it was discovered that there had been a break-in at No.18

as well. Police made the reasonable assumption that whoever had broken into the

Watts house had most likely broken into the Martins also, and the Martins crime

scene had all of Manuel’s hallmarks. Police went straight to Manuel’s home with

a search warrant for the .38 revolver. As usual both Peter and Samuel

complained about police harassment and denied any knowledge of the crime, and

the police turned up nothing in their search. Meanwhile the newspapers reported

every gory detail of the crimes breathlessly, and several neighbours of the

Watts fitted extra bolts to their doors, terrified that the unknown killer

might strike again.

When

news of the murders began to break, before police could officially notify the

family of the victims, a journalist managed to get hold of the home number of

the husband of murdered Margaret Brown, who was at work and did not yet know of

the tragedy. Perhaps it was the same tactless journalist that called the

Cairnbaan hotel claiming to be a business associate of Mr Watt. Luckily, Watt’s

brother John was able to get hold of William and break the terrible news to him

before the journalists could. He reportedly broke down before being driven back

to Glasgow by police. It was during this drive that police began to become

suspicious of William’s demeanour in the face of such a devastating tragedy. One

detective reported that instead of the broken man he expected to see he found

instead ‘a man with a smirk on his face and no tears.’

This was to compound police

suspicions that Watt was somehow complicit in the murder of his family. On

September 24th the Evening

Times reported the police’s belief that the victims had somehow recognised

their killer, laying the seeds for a monumental decision they would make in 4 days’

time. On the 28th of September 1956, only 3 days after he had

attended the funeral of his family, William Watt was charged with the murders

of his wife, daughter and sister-in-law. During his brief appearance at Glasgow

Sherriff court, Watt did not speak. When he emerged to be taken to Barlinnie

prison he was greeted by a 200 strong crowd booing loudly, many of whom had

waited seven hours to catch a glimpse of the man they thought responsible for

the horrific triple murder.

Why then did the police belief that it was possible that William Watts, who although he admitted to several instances of infidelity during the course of his marriage was by all accounts a loving father, could have driven 180 miles overnight to coldly murder his family as they slept in their beds, before driving back to the hotel to play the part of the grieving widow and father?

Why then did the police belief that it was possible that William Watts, who although he admitted to several instances of infidelity during the course of his marriage was by all accounts a loving father, could have driven 180 miles overnight to coldly murder his family as they slept in their beds, before driving back to the hotel to play the part of the grieving widow and father?

|

| The Cairbaan Hotel |

On

the night of the murder Watt spent his time fishing, meeting friends and

watching television before having a dram or two of whisky with owners of the

Cairbaan hotel. The day before the murders Watt had filled his car with seven

gallons of petrol, an action that may have seemed suspicious considering he had

arrived at his destination and had no plans to return home for several days.

However he also informed the mechanic of faults with the engine and lights of

his car, conditions which would have been less than ideal for a lengthy clandestine

over- night drive. During his holiday he had called home every couple of days,

and on the night of the 16th he did so again and spoke to his wife,

Marion, who told him that her sister, Margaret, was staying with them

overnight, and they discussed whether William should stay another week at the

hotel. He told police that he had sat drinking with the hotel owners until

around 12.30am before borrowing and alarm clock from the kitchens and setting

it for 6am, with the intention of doing some fishing in the morning. One of the

hotel waitresses reported seeing Watt at his window at around 1am. Watt would tell

police that he had turned off the alarm clock in the morning, but this was later

found to be wrong. Watt had either been innocently mistaken, had slept through

the alarm, or, as the police suspected, simply wasn’t in the bedroom when the

alarm sounded, as he was miles away murdering his family. After the sighting by

the waitress at 1am, Watt was next seen at 8.10am by a waitress at the hotel

clearing frost from his windscreen, something that might have been unlikely had

the car been running all night.

In an

effort to prove Watt’s guilt, a police driver was later able to demonstrate

that it was possible to cover the route from the hotel to the Watt family home

in two hours and four minutes, affording Watt just about enough time to wipe

out his family before driving back to the hotel to pretend he had never left.

However, the police did not use a Vauxhall Velox for the test drive, but a Ford

Zephyr instead.

If

the 1am sighting by the waitress is to be believed then police must have

supposed that Watt had somehow slipped out of the hotel unseen at some point

after 1am, bundled his pet Labrador into the car, had driven 180 miles home, murdered

3 members of his family one by one, before breaking the glass at the front door

to stage a break-in and driving all the way back to the hotel, slipping in

unnoticed in time to appear again in the morning as if he had never left. It

also appeared that if Watt had really driven the 180 miles back to Glasgow, he

had done so without lowering the fuel level. All garages in the area were

checked to see whether he had filled up but none reported seeing him, and

supposing that instead Watt carried a secret supply of fuel cans, none of them

were found either. Police frogmen also dredged the Crinan Canal in the hopes of

recovering the murder weapon or bloodstained clothing, but neither were found,

for the gun used to kill the Watt family was actually lying in a different

stretch of water 90 miles to the South. A spot of blood found on Watt’s hotel

bed became the focus of intense police suspicion, but Watt explained it away by

telling police it came from a corn on his foot.

Convinced

of Watt’s guilt, police appealed to the public for anyone who had seen Watt

during his 180 mile homicidal journey to come forward – and two duly did. The

ferryman on the Renfrew Ferry came forward to report that he remembered taking

a lone male driver across the Clyde at around 3am on the 17th

September 1956. If Watt did leave the hotel at 1am then the sighting on the

ferry would almost be perfect timing. Furthermore, according to the ferryman

there was a black dog in the car, and Watt had his pet Labrador Queenie with

him on holiday. Even more convincingly, the ferryman picked out Watt’s Vauxhall

Velox out of a line-up of 24 cars before following that feat up by identifying

Watt himself out of a line-up of 9 men. Of course, these details, the make of

the car, the fact that Watt had a dog, could have been gleaned from the

newspapers, something that the ferryman strenuously denied. Despite the

extensive press coverage, he claimed to have never seen a photograph of Watt or

his car. However, Taylor was later to change his story and claim that it was in

fact a Wolseley, and not a Vauxhall, that he had carried across the river that

night. When the police drivers conducted the test-drive from Watt’s hotel to

the Watt home in Burnside to determine whether it was possible for him to have

committed the murder, the route they took did not include the Renfrew Ferry,

which, if the ferryman sighting was indeed Mr Watt, would have been the route

he took. If they had included the ferry it would have added a considerable

portion of time to the journey, and, supposing that Watt was driving into

Glasgow with the intention of murdering his family, why would he risk contact

with potential witnesses by taking the manned ferry?

With

Taylor’s sighting falling apart, police appealed for anyone else to come

forward with any sightings of Watt on the night of the murder. They were

approached by a man named Roderick Morrison who told them that he had been

travelling north to Fort William with his wife and driving along Loch

Lomondside at around 2.30am on the morning of the 17th, when he

noticed a car speeding southwards towards him. The speeding car suddenly disappeared,

Morrison thought it may have crashed off the road before he saw it parked at

the roadside with its lights off. Morrison stopped his car and approached the

other vehicle, inside he saw a lone male occupant smoking a cigarette who

shielded his face from the glare of Morrison’s headlights. Before he could get

close enough to speak to the driver, the car suddenly switched its lights back

on and sped off. Morrison thought that the car he saw was either a Standard or

a Vauxhall, and police mused that one explanation for the car suddenly pulling

over was that the car’s lights had temporarily failed – the same fault that

Watt had reported to the mechanic the day before. Morrison identified Watt out

of a 30 strong identification parade due to the fact the Watt was the only one

to hold his cigarette in the same peculiar manner to the man Morrison had

encountered. However, he did later admit that he had never actually had a clear

view of the face of the driver.

|

| William Watt |

Yet Despite

the lack of motive, evidence, reliable witnesses or means, William Watt was arrested

and charged with the murder of his entire family and sent to Barlinnie prison

to await trail, he would eventually be released without charge when collective

sanity was resumed. But at the time Peter Manuel must have thought the stars

were aligned in his favour. He had wriggled out of the Mary McLachlan rape

trial, police had failed to pin the Anne Kneilands murder on him, and now police

seemed to be determined to pin the murder of the Watt family on the innocent

William Watt. Manuel must have felt cockier than ever, and so - sure of his

ability to outsmart the authorities - he determined to insert himself into the

investigation and taunt both the police and William Watt.

Manuel

wrote to the police claiming he knew who had committed the murder, he also

contacted several newspapers claimed to have insider knowledge of the crime. He

even arranged to have a meal with Watt and his lawyer at Glasgow’s Whitehall

Restaurant to discuss the case. He claimed that a criminal associate, who he

was conveniently unable to name, was responsible for the crime, while simultaneously

providing an impressively detailed description of the Watt home, a description

which he claimed had been passed on to him by the perpetrator. In one piece of bizarre behaviour, during one

of these meetings with Watt, Manuel produced a photograph of his first murder

victim Anne Knielands, asking Watt if he knew her, before ripping the

photograph to pieces.

While

both the police and William Watt were suspicious of Manuel’s intentions, and suspected

that he knew more about the crime that he was telling, equally, they supposed

that it was possible that the information he was taunting the authorities with

was simply gleaned from the newspapers, there was no physical evidence against

him after all. And so Manuel was free to go on and murder 5 more people, and to

wipe out a family in their beds as they slept one more time.

That bungalow has been the home of my second cousin for many years. Prior to knowing the story, I often wondered each internal door had a a lock on them. My late Mother was a friend of the two Italian sisters who resided next door.

ReplyDeleteInteresting. This guy was a monster. Don't know if I could live in a house where murders took place

Delete